Self-management not only means to deal with the current condition, but also pursuing a holistic approach to mental and physical wellbeing. Self-management complements medical treatment to become more effective and successful. “Self-management has empowered me to better know and understand myself on so many levels” explains Jacqueline Bowman-Busato in her contribution.

For at least the past 23 years, I’ve been living with two complex chronic, relapsing diseases: Autoimmune Hashimoto’s and obesity. And yet, I can only say that it’s been the last 18 months where I have finally felt in control of my two diseases in any meaningful way. And this has been due to finally understanding and embracing responsible self-management.

Let me explain from a patient’s perspective. When I consciously started the journey of firstly realising that I had “a thyroid problem” which eventually was diagnosed as autoimmune hashimotos, I didn’t understand that a simple pill wasn’t enough to minimise symptoms. Critically, none of my medical specialists seemed to know or care about this fact either. The resultant search for energy in the wrong places aggravated my hashimotos symptoms (severe malabsorption of vitamin D and B as well as iron which all present as depression and severe anxiety). And all very quickly led to developing obesity. I never discussed obesity with my GP for 20 years (the average is 6 years according to a new study Action IO). I “dealt with it” by following holistic diets which always had a beginning, middle and very quick end!

It´s time to change

It was not until 18 months post bariatric surgery on 4 July 2016 that everything finally clicked into place for me. I realised that regardless of the good intentions of the public health environment, the sad fact of today’s chronic disease environment is medical treatment of physical manifestations rather than a holistic approach to mental as well as physical wellbeing, not to mention a lack of positive motivation to work together with health professionals in an empowering and empowered way.

Self-management has meant that I have had to take a very long and hard look at myself, the good, the bad and the very ugly truths in order to forge a personal pathway towards managing my life in such a way to optimise my mental health and wellbeing. Armed with my newly gained (and acknowledged) self-knowledge, I forged my own objectives-driven processes for achieving my goal of “mental clarity”. For me, brain fog has been my biggest barrier to sustainable management of both hashimotos and obesity. Having an objective of brain clarity rather than weight or specific blood values has meant that I’ve been able to take control of my health much more than if I solely relied on medication and then wondered why I was still malnourished to the point of continuing to seek energy in foods which are basically poison to me. Giving myself parameters with well-defined processes has significantly empowered me and raised my confidence levels to collaborate with my health care team. I am now listened to and heard.

Jacqueline Bowman-Busato

As a patient representative, Jacqueline has advised the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) on patient engagement strategy, and provides expert advice to the European Commission on self-care policies. She works extensively on European as well as global projects bringing the key stakeholders together to build lasting consensus on global, regional and national levels.

Empowerment through self-management

Science very clearly states that obesity is a chronic relapsing disease. It‘s not the fault of one or other individual. In my world, that does not mean that I have to accept whatever medication I’m given in isolation. It means that I use the treatment (in my case the radical treatment of bariatric surgery) as a tool and I supplement with my own process for mental and physical wellbeing to put me on an even playing field to be able to optimise the medical treatment. Self-management empowers me to engage with the system and my health professionals. It allows me to give myself a bit of certainty which is not anxiety causing. It allows me to feel a partner in my own health. Self-management has empowered me to better know and understand myself on so many levels.

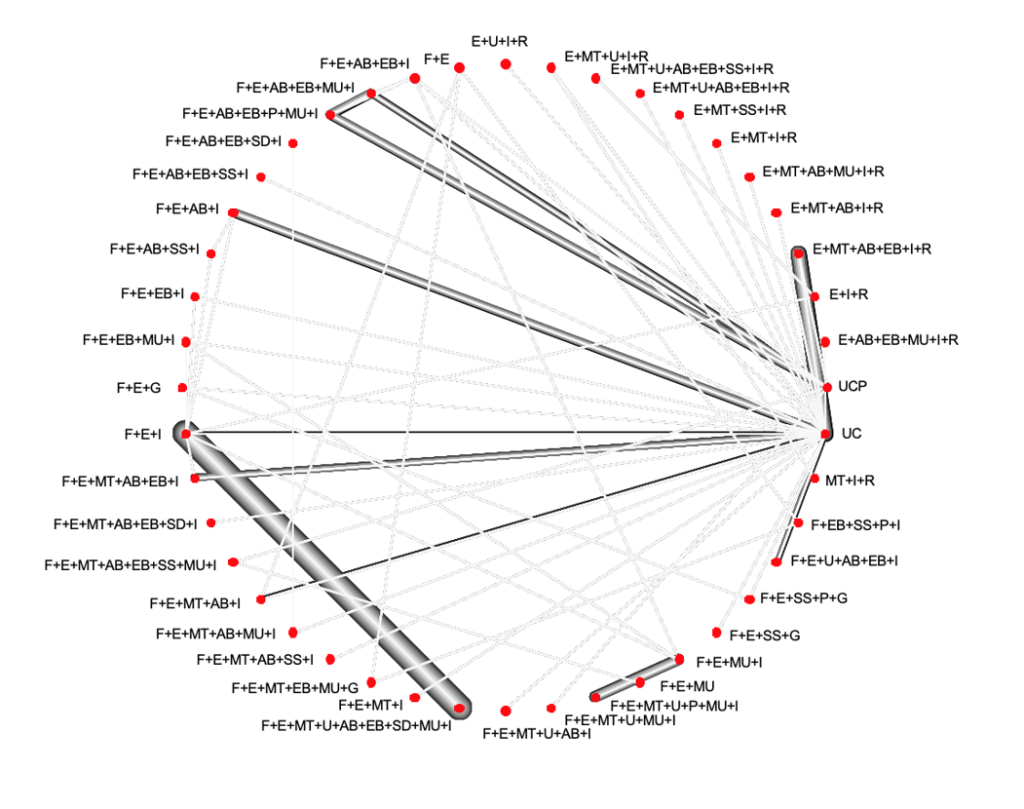

This network plot shows which interventions are compared. Nodes represent SMIs and the edges between the nodes represent comparisons that have been evaluated in the included RCTs. The thickness of the edges is proportional to the number of participants randomized to the respective comparison.

This network plot shows which interventions are compared. Nodes represent SMIs and the edges between the nodes represent comparisons that have been evaluated in the included RCTs. The thickness of the edges is proportional to the number of participants randomized to the respective comparison.