Multi-component SMIs

SMIs are multicomponent interventions and they are determined by their characteristics (support techniques) and the context under which they are applied (e.g. type of encounter, mode of delivery, type of provider, intensity). It is our goal in COMPAR-EU to

- locate those components that work (or do not work) and

- explore how these components interact with each other.

To this end, we employed network meta-analyses models. The main benefits of network meta-analysis is that it synthesizes both direct and indirect evidence and results in more precise effect estimates compared to those of pairwise meta-analyses.

Sparse networks

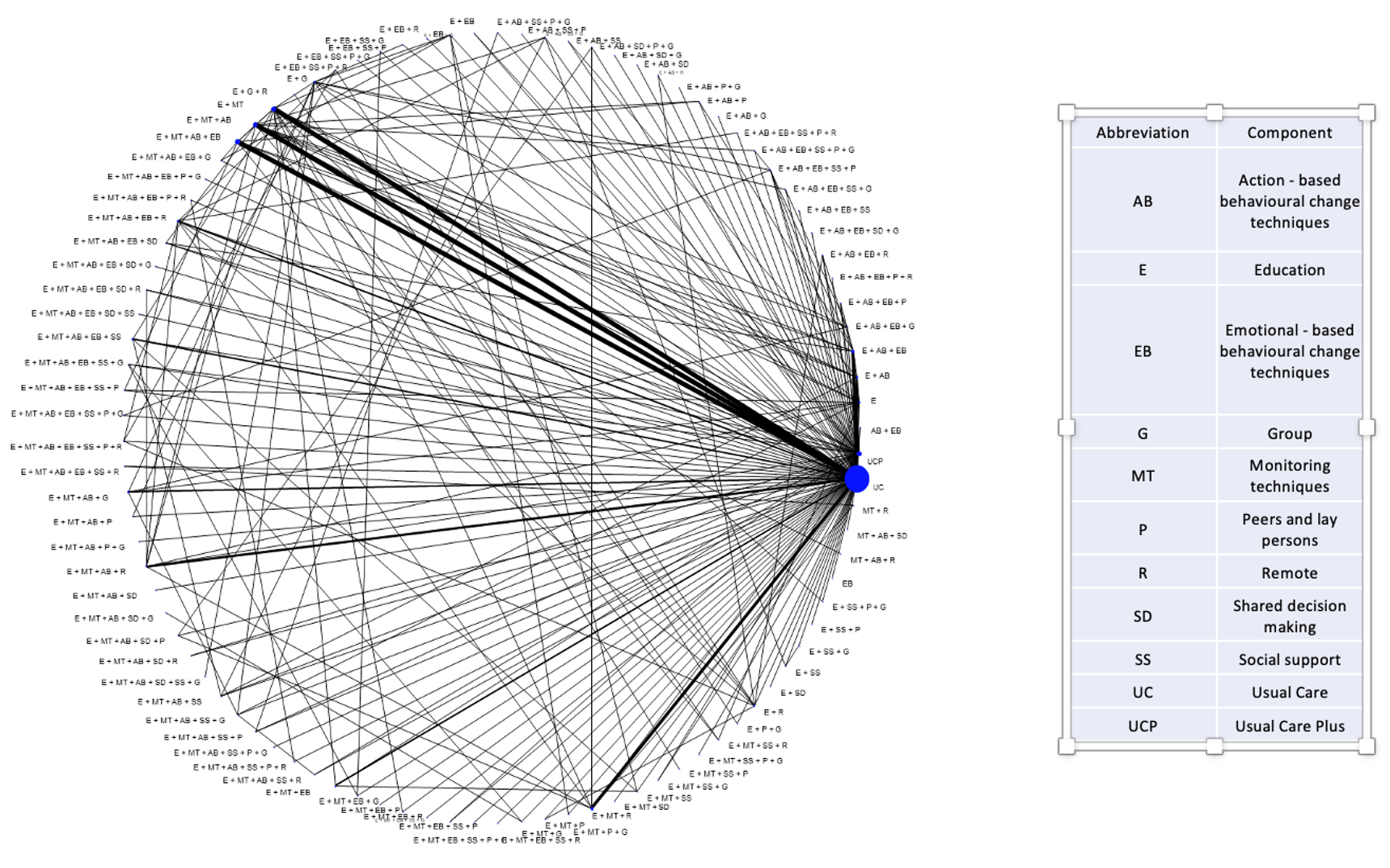

SMIs are very heterogeneous interventions. They typically form sparse networks with each combination of components observed only in a few studies. An example of a network of SMIs depicting a network of 461 randomized clinical trials comparing a total of 97 distinct SMIs for the reduction in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) is shown in the Figure below. Nodes represent interventions (combination of components in this case) and edges represent direct evidence (trials directly comparing the interventions shown in the connecting nodes). Size of nodes and thickness of edges is proportional to the information the network provides for the respective intervention and comparison. Information flows across the network and each trial informs the entire network. Out of these 461 trials, 386 (84%) compare an SMI to usual care. This is why we note a large node for “usual care”. The remaining nodes are poorly connected to each other. A relative effect for a pair of SMIs (a line in the Figure) is informed mainly by those studies (usually one or two) that compare this pair. As a result, this NMA estimate depends heavily on what is observed on these trials and as this is the case for most pairs of SMIs, we infer that NMA results are heavily confounded with study characteristics. This compromises the main assumption in NMA; the distribution of effect modifiers is similar across treatment comparisons.

Consider there is a small trial comparing a SMI (e.g. comprising education and shared decision making techniques, done remotely by a non-professional) to “usual care”. This study has a large effect maybe because its population is severely ill or the population is a certain minority group or the duration and intensity of the SMI is very large or even for reasons such as fraud or poor methodology. The NMA effect for that intervention would be very large just like what we observed in the trial just because the rest of the network will not provide much information (if any at all) for this NMA effect. This result would be misleading as the remaining studies in the network have other characteristics. But what drives the effect of this SMI are the study characteristics and not the SMI per se.

Evaluating components’ effectiveness

The classical interpretation of NMA effects won’t be of much help in sparse networks of multi-component SMIs such as those we deal with in COMPAR-EU. Not only efficacy is confounded with study characteristics but we also get very imprecise NMA effects as there is little flow of information.

Component network meta-analysis

Alternative evidence synthesis models have been developed that aim to estimate the effect of each component (component NMA -CNMA). Each component is included in many trials and all these trials will inform its relative effect. Hence, we get very precise effects. Unfortunately, problems do not just vanish into thin air

- We don’t know how components interact with each other (mathematically we assume that components have an additive effect, an assumption that is hard to test and/or defend). Even if we identify the “perfect” SMIs by combining those components with large effects, we do not know how these will perform in practice.

- The context and conditions under which a SMI is applied is of paramount importance. Hence, confounding may still be an issue, especially if a component is included in a few trials. Most probably the contextual factors would reveal themselves in large statistical heterogeneity compromising the validity of results and making interpretation difficult.

Visual inspection of NMA results.

A visual inspection of the NMA results may reveal important information regarding which components work and interact well with each other. For example, if most of the SMIs with large effects are applied face-to-face whereas those with small effects are applied remotely, this is an indication that face-to-face is working. This is not an easy task and we have developed a series of results and graphical methods to disentangle those components which are associated with large effects from those that are not.

When I realized that in COMPAR-EU we will be working with networks of hundreds of studies I felt I hit the jackpot. In practice, with so many known and unknown effect modifiers, components and nodes in the network, it is easy to downplay uncertainty and hard to separate signal from noise. A famous aphorism in statistics, attributed to British statistician George Box, is “All models are wrong, but some are useful”. The aphorism recognizes that we cannot perfectly model the complex systems of reality but we can still get some useful information. Our results, from many NMAs on many outcomes, include a wealth of information!

Dimitris Mavridis

Dimitris Mavridis is an Assistant Professor in statistics for the social sciences at the Department of Primary School Education at the University of Ioannina. He has published more than 40 papers relevant to network meta-analysis (NMA). His works include both methodological papers and applications of NMA in various fields.